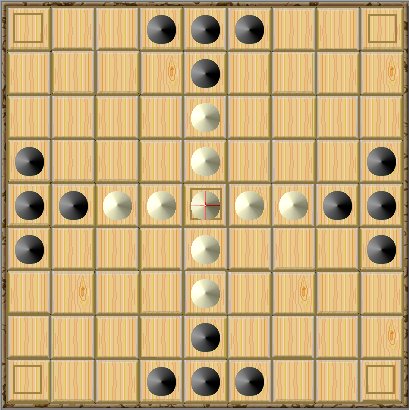

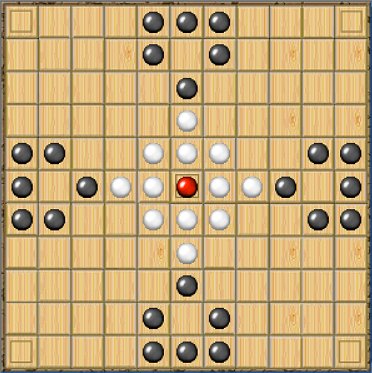

In Tablut (also Hnefatafl ) the Black

side is laying siege to the kingdom of the White side. The object

for the White side is to move his King (“Hnefi”) to

one of the corner squares, in which case he has successfully

escaped. The object for the Black side is to capture the White

King. Black makes the first move. All pieces move like a Rook in

chess, that is, any number of squares horizontally or vertically.

No pieces, except the King, may land on the corner squares or the

centre square. The centre square is the King’s throne or

“Konakis”.

Tablut employs orthogonal interception-capture. When an

enemy piece is surrounded on two opposite sides, the piece is

captured. The corner and centre squares also act like friendly

pieces. Thus, if an enemy piece is sandwiched between a friendly

piece and these special squares, this also results in capture.

Capture is not mandatory. Note that the central square

only functions as capture square when it’s empty. (In an

alternative variant, it needn’t be empty to function as

capture square.) The same capture rules applies also to the King,

except when it is positioned on the centre square, when it must

be surrounded on all four sides. If the King is positioned on any

of the four squares adjacent to the centre, it must be surrounded

on three sides, plus the centre square, which then functions as a

capture-square.

Tablut boards and pieces are often found in Viking graves. Pieces

are typically made of bone, glass, or amber. The game had a rich

history in Viking tales. In one such story King Knut and

Jarl Ulf were playing, and Knut made a mistake allowing Ulf

to capture a piece. Knut requested that he be allowed to take

back his move. Ulf refused, toppling the board, and an argument

ensued that ended when Ulf was killed. The Swedish botanist

Carolus Linnæus, the inventor of the system for

classifying plants and animals we still use today, wrote about

Tablut in his diary in 1732. He discovered it during his travels

in Lapland, where the game had survived and was still played

among the Lapps. The side with the King represented the Swedes,

while the other side respresented Moscovites.

Watch out whenever a piece is positioned orthogonally adjacent to

an opponent’s, as it’s liable to get captured.

Exchanging pieces early in the game would generally benefit White

rather than Black, because White needs open space to escape with

his King. Black should keep the position crowded. Both sides

should look out for King moves that allow the King two different

paths to the rim, since it will be impossible to block both

directions at the same time.

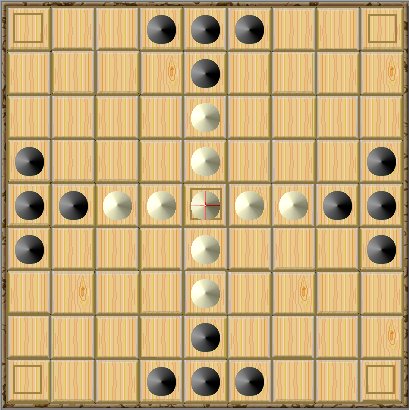

Five variants have been implemented: Tablut (9x9), Brandubh

(7x7), Large Hnefatafl (13x13), Tawlbwrdd (13x13) and Alea

Evangelii (19x19). Tablut (above image) seems to be a

well-balanced game. It’s a tough nut to crack, although

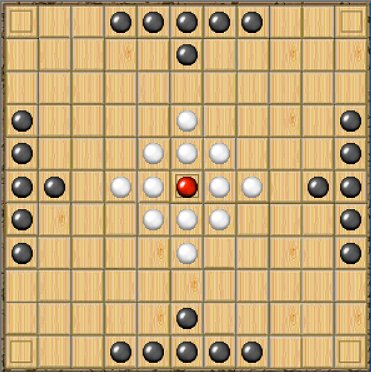

Black should probably win in the end. In Brandubh (below)

White can sometimes achieve a rapid win, but Black’s

chances seem slightly better. White could build a fortress,

making the king invulnerable, with the intent of repeating moves

within the fortress. But this only means that White has lost;

since there is no way out and there are only two results: win or

lose. If White repeats moves, he loses, too.

Tablut and Large Hnefatafl derive from Scandinavia and are

probably more original than Brandubh and Alea Evangelii (The

Evangelic Game), which were played on the British islands. In

Alea Evangelii the rules differ somewhat, and White starts the

game. This implementation follows the rules researched by the

Historical Museum, Stockholm, and it shows what a sophisticated

game Tablut is. It was immensely popular during the Viking

era.

There are two other versions of the game, with similar rules,

namely the British gwyddbwyll and the Irish

fidhchell. They figure in many stories in the Celtic

tradition. The corner squares were regarded as the four

Otherwordly cities to which the Tuatha de Danaan arrive.

It was a godlike idealized people around which many heroic

stories revolve. On the gaming board, which was also the land,

the center is regarded as sacred and called Tara, the seat

of High Kings. As the mystical fifth dimension it represented the

Otherworld itself, which was always proximate, and overlying

reality (cf. Matthew, C., “The Celtic

Tradition”, pp.9-10).

Brandubh (“black raven”)

is Irish and is quite a sophisticated game. It is much more

complicated than one would expect.

Brandubh (“black raven”)

is Irish and is quite a sophisticated game. It is much more

complicated than one would expect.

Large Hnefatafl derives from

Scandinavia. A game of this size would probably call for training

from early age. It appears that Viking boys trained

“swimming and playing tafl”. Tafl is the oldest name

for Hnefatafl.

Large Hnefatafl derives from

Scandinavia. A game of this size would probably call for training

from early age. It appears that Viking boys trained

“swimming and playing tafl”. Tafl is the oldest name

for Hnefatafl.

Tawlbwrdd was played in Wales. Only

the setup differs from Large Hnefatafl.

Tawlbwrdd was played in Wales. Only

the setup differs from Large Hnefatafl.

Alea Evangelii (“The

Evangelical game”) derives from 10th century England.

Christian interpreters viewed it as an allegory of the

Evangelists. The primarius vir (the king) symbolized the

unity of the Trinity. In reality it was played on the

intersections of an 18x18 board, which makes 19x19 positions

(actually, a Go board). The rules for this variant are different.

If the white King reaches the rim the game is won. The whole

periphery functions as capture square. White makes the first

move.

Alea Evangelii (“The

Evangelical game”) derives from 10th century England.

Christian interpreters viewed it as an allegory of the

Evangelists. The primarius vir (the king) symbolized the

unity of the Trinity. In reality it was played on the

intersections of an 18x18 board, which makes 19x19 positions

(actually, a Go board). The rules for this variant are different.

If the white King reaches the rim the game is won. The whole

periphery functions as capture square. White makes the first

move.

References

Murray, H.J.R. (1952). A History of Board-Games Other Than

Chess.

‘Tafl games’. Wikipedia article. (here)

See also: Breakthru – a modernized version of medieval Tafl (here).

☛ You can download my free Tablut program here (updated 2025-05-15), but you must own the software Zillions of Games to be able to run it. (I recommend the download version.)

© Mats Winther 2006